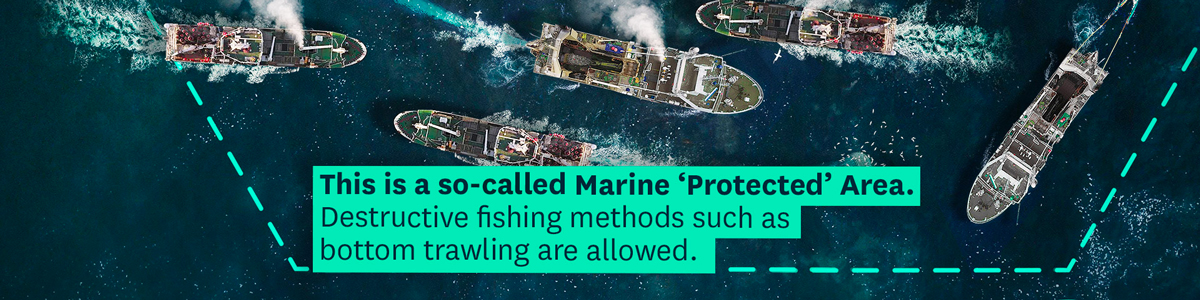

A Marine Protected Area (“MPA”) is “a clearly defined geographical area, formally recognized, dedicated and managed through legal or other effective means, aiming to ensure the long-term conservation of nature, and of the ecosystem’s services and cultural values associated to it”.(1)

According to the IUCN, a “Marine Protected Area” cannot be considered as “protected” if industrial extractive activities (including fishing) are conducted there or if industrial infrastructures are developed.(2) An MPA therefore bans industrial fishing at the very least, defined by the IUCN as fishing carried out by vessels over 12 meters long, 6 meters wide or using towed gear.(3) Depending on the level of protection afforded to an MPA, artisanal fishing may be permitted.

THE OCEAN, OUR ALLY FOR THE CLIMATE

The ocean and marine ecosystems are at the heart of the fight against global warming.

- The ocean absorbs more than 25% of our greenhouse gas emissions and is the main regulator of our planet’s climate.(4)

- The ocean captures more than 90% of the excess heat generated by human activities.(5)

- The ocean thus acts as a thermostat for the planet, but global climate change threatens its ability to fulfill this function as effectively in the future.

To destroy the ocean is to collectively condemn us all.

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS, THE KEYSTONE OF MARINE BIODIVERSITY

In the absence of extractive human activities, marine protected areas enable a spectacular regeneration of marine ecosystems and species:

- Fish biomasses in marine reserves are on average 670% higher than in surrounding unprotected waters!(6)

- This regeneration creates a spillover phenomenon with marine populations spreading outside the protected area, thus contributing to the recovery of biodiversity and marine ecosystems.

PROTECTING AND FISHING: INSEPARABLE PRACTICES

By protecting the ocean, MPAs also protect fishing, since they favor artisanal fisheries(7) which represent the majority of the global, European and French fisheries in terms of number of jobs and number of vessels.(8)

- MPAs with a high level of protection (strong or full protection in the MPA Guide(9)) can “increase the productivity of the fishing zones around the protected area through the proliferation of adults and larvae […] including in overfished areas.”(10)

- According to Eric Sala, explorer and conservationist at National Geographic, “In the assumption that there would be a total displacement of fishing effort, strategically placed marine areas covering 28% of the ocean could increase the supply of marine food resources by 5.9 million tons per year compared to a business-as-usual scenario with no additional protection and undiminished fishing pressure.”(11)

- MPAs enable an equitable, long-term redistribution of resources and socio-economic benefits between the various uses of the territory.(12)

By banning industrial fishing, the benefits provided by MPAs far outweigh the costs involved in setting up or running the protected network, or the costs associated with relocating and reducing industrial fishing effort.

- The benefits associated with banning bottom trawling in EU MPAs have been estimated to be positive as early as the fourth year after the ban was introduced. The economic benefits would reach a maximum net value of 600 million euros.(13)

- As early as 2003, at the IUCN World Parks Congress in Durban, scientists estimated the need to protect 20%-30% of all the world’s marine habitats, including the high seas, through strict protection zones.(14) In 2004, the annual cost of establishing, managing and monitoring such a network of MPAs was estimated at between US$5 and US$19 billion, less than the amount allocated by governments to finance industrial fishing. Moreover, this estimate did not even take into account the social benefits associated with tourism and the restoration of adjacent artisanal fisheries.

(1) Day et al., “Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas”, 2019. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/PAG-019-2nd%20ed.-En.pdf

(2) “The World Conservation Congress […] CALLS ON governments to prohibit environmentally damaging industrial activities and infrastructure development in all IUCN categories of protected area”, IUCN (2016) IUCN Resolutions, Recommendations and other Decisions -World Conservation Congress, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, United States of America

(3) IUCN (2021) Guidance to identify industrial fishing incompatible with protected areas

(4) IPCC (2019) Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) — Summary for policymakers

(5) Ibid.

(6) Eric Sala and Sylvaine Giakoumi. “No-take marine reserves are the most effective protected areas in the ocean.” ICES Journal of Marine Science 75.3 (2018): 1166-1168.

(7) Claudet (2006) Spatial management of inshore areas: Theory and practice

(8) FAO (2022) Small-scale fisheries and sustainable development ; STECF (2021) The 2021 Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet ; FranceAgriMer (2021) Chiffres-clés des filières pêche et aquaculture en France en 2021

(9) Kirsten Grorud-Colvert et al. (2021) The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean

(10) IUCN « Les Zones de protection forte en mer, état des lieux et recommandations ». 2021. Available at: https://uicn.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/rapport_final_zpf-070921.pdf

(11) Eric Sala and Sylvaine Giakoumi. “No-take marine reserves are the most effective protected areas in the ocean.” ICES Journal of Marine Science 75.3 (2018): 1166-1168.

(12) Davies et al. (2021) Valuing the impact of a potential ban on bottom contact fishing in EU Marine Protected Areas.

(13) Ibid.

(14) International Institute of sustainable development (2003) Summary report of the Vth IUCN World Parks Congress : benefits beyond boundaries 8-17 September 2003