WHAT’S THE REALITY BEHIND THE STATE’S AMBITIOUS GOALS?

Because marine protected areas (MPAs) offer many advantages, sates have mobilized to make them a key lever in the fight against climate change and the erosion of biodiversity – at least on paper.

The will to protect the ocean took a leap forward at the 10th Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity (“CBD”) in Nagoya in 2010, where states adopted a plan which commits to conserving 10% of coastal areas.(1)

These objectives are currently being revised upwards to reach the protection of 30% of the seas and oceans by 2030, as recommended by the IUCN.(2) These new quantified targets should be adopted during the 15th Conference of the Parties of the CBD.

However, between political promises and reality, the gap is immense: at the global level, only 2.4% of the ocean is strongly or fully protected from the impacts of fishing and other extractive activities.(3) In response to this disintegration of ocean protection objectives, the international scientific community has produced a classification of MPAs according to their degree of conservation and implementation.(4) This work has revealed, behind the rhetoric, the disastrous state of so-called “protected” marine areas in Europe and France.

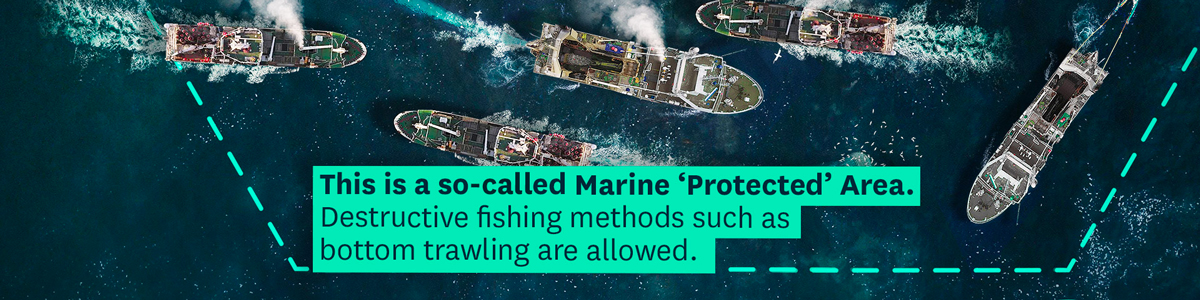

INTENSELY EXPLOITED “PROTECTED” AREAS

Today in Europe, “protected” marine areas suffer devastating industrial fishing gears that scrape the seabed and destroy ecosystems, such as bottom trawls or demersal seines (a method similar to trawling):

- 86% of Europe’s so-called “protected” areas are intensively exploited by destructive fishing methods.(5)

- In more than 2/3 of the MPAs in northern Europe, trawling is 1.4 times more intense inside the supposedly protected area than outside!(6)

In France, the situation is not any better. In 2021, almost half of the fishing effort by vessels over 15 meters long took place in marine protected areas in mainland France.

Fishing intensity was even higher in 2021 in Natura 2000 sites and marine nature parks, recognized symbols of a protection model “à la française”, than in unprotected areas.

The ‘protected’ marine areas heralded as examples by France, such as the Mer d’Iroise marine park, are totally ineffective in protecting the marine environment.

A NEAR-ZERO PROTECTION IN FRANCE

France is remarkably mediocre in terms of marine protection. Although the country is the world’s second largest maritime power (due to the immense size of its EEZ), France is ranked 17th regarding our MPA ratio. While The United States protect 23% of its EEZ and that the UK sanctuariser 39% of its waters (see the MPA Atlas), France truly protects less than 4%.

The few French marine areas that are truly protected are never located in the areas that need it most, i.e. where strong fishing pressure is impacting biodiversity and marine ecosystems. They are generally located in remote areas where human activities are not very intense, such as the remote waters of the Southern Ocean.(7)

In metropolitan France, the percentage of real protection falls to an almost non-existent level: in the Channel as well as the Atlantic and North Sea, only 0.005% of French waters are really protected!(8)

Thus, although marine protected areas (MPAs) are essential solutions for restoring ocean biodiversity, marine habitats and the planet’s climate, it is clear that their implementation has been a failure: today, the vast majority of so-called ‘protected’ French marine areas are not protected at all.

THE IMPOSTURE OF FRENCH-STYLE STANDARDS

Instead of complying with international standards for the classification of marine protected areas, France has generated a French exception: a tailor-made classification of protection levels – 11 in total!(9) – which results in incomprehensible and above all totally ineffective statutes.(10) This imbroglio has very concrete effects: it allows industrial fishing companies to continue their activities without being hindered by protection zones. As a result, in 2021, 47,2% of industrial fishing took place in so-called “protected” marine areas!

Reshaping the protection classifications allows President Macron to trumpets that France exceeded the 30% protection goals without having to protect the ocean.

A telling example of sabotage is the decree on the definition of “strong protection” that replaces the “strict protection” recommended by the European Comission. While Emmanuel Macron proudly announced on February 11, 2022 in Brest that the country would catch up on its “strong protection” goals,(11) the government had already destroyed the very definition of what constitutes a “strong protection”. In a paroxysm of political cynicism, the Ministry of Ecological Transition had not only already drafted a technically perverse decree to demolish the notion of “strong protection” in France, but had even closed the public consultation period on the text before the President’s announcements.(12)

The French strategy of sabotaging international standards came to an end in Montreal at COP15 for biodiversity. The EU delegation – supported by France and the Netherlands among others – refused to defend the European Commission’s recommendations for the strict protection of 10% of the oceans. France, gripping tightly to its hollow definition of ‘strong protection’ and its protection model ‘à la française’, campaigned for the 30% target for ocean protection adopted at COP15 to be a superficial target with no mention of the quality of said protection.

The empty ambition of the ‘global framework for biodiversity’ adopted in Montreal only reinforces France’s protection model. A model which, behind a multitude of MPA categories and a complex maze of fishing regulations at sea and in so-called ‘protected areas’, fully serves the interests of industrial fishing.

Indeed, rather of complying with international standards for the classification of marine protected areas, the French government avoids defining what a marine protected area is at all costs, and what should be prohibited in such an area. Instead of a clear and precise framework for the protection of the oceans (a framework already established by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – the French Environmental Code establishes a non-exhaustive list of protection tools with multiple objectives, fields of application and sources of law. There are at least 14 distinct categories of protection in metropolitan France, while the IUCN recommends six(13) and the scientific community four.(14)

Worse still, none of these categories systematically prohibits industrial activities, so much so that none can be considered a true marine protected area by international standards. Reshaping the protection classifications thus allows President Macron to claim that he has exceeded the 30% MPA target, without having to protect the ocean.

The model of exception ‘à la française’ cultivated by the government and representatives of industrial fishing is also characterized by an imbroglio of regulatory texts, a thicket of exceptions, derogations and specific regimes of all kinds that are impossible to untangle and that keep any appropriation of the subject by public opinion at bay. This imbroglio has the very concrete effect of allowing industrial fishing companies to continue their activities without being hindered by protected areas.

Emmanuel Macron’s government is thus organizing the impotence of the very concept of ‘protected’ marine areas and orchestrating the conditions of French imposture vis-à-vis international scientific recommendations and European environmental protection objectives.

HYPOCRISY WITH REAL CONSEQUENCES

DISASTROUS FAILURES FOR MARINE ECOSYSTEMS, FISHERS AND THE PLANET

The weak or non-existent protection offered by MPAs is first of all devastating for marine ecosystems, which do not find relief from the pressure of high-impact human activities such as industrial fishing, the first cause of ocean destruction.(15)

Moreover, as biodiversity is eroding and as fish stocks collapse, artisanal fishers are seeing their source of livelihood disappear, leading to the disintegration of the coastal socio-economic fabric. For some developing countries that are heavily dependent on fishing, this even causes serious problems of food insecurity.

At a time of global warming, the imposture represented by a majority of MPAs, which allows fishing gear such as bottom trawling, is all the more problematic as marine sediments constitute the largest carbon sink in the world. Biodiversity experts gathered in the Intergovernmental Science Platform IPBES warn that “global sediment carbon emissions after 1 year of trawling are […] equivalent to about 15-20% of the atmospheric CO2 absorbed by the ocean each year”.(16)

How can the ocean play its essential role as climate regulator if we do not protect it from climate-damaging fishing practices?

MILLIONS OF EUROS WASTED

Although ineffective and even counterproductive, fake marine protected areas are resource intensive. In France, BLOOM was able to reconstruct that at least 5.3 million euros of European funds had been allocated to the French Office of Biodiversity and its predecessors for the establishment of areas that only exist on paper. Natural marine parks in the metropole that cover 6,5% of French waters, alone represent an annual investment of 500 000 to 1 million euros depending on the park. (17)

EMERGENCY

This alarming state of affairs reflects not only the fishing industry’s great resistance to the very principle of protection, but also its unacceptable weight in shaping government measures. At a time when biodiversity and climate researchers (IPBES and IPCC) warn of the irreversible consequences of inaction for the planet and for humanity, it is our duty to take relentless action to obtain public policies capable of protecting humanity from unprecedented disruption.

References

(1) COP10 of the Convention on Biological Diversity, «Décision adoptée par la conférence des parties à la convention sur la diversité biologique à sa dixième réunion», 2010.

(2) UICN, «WCC-2016-Res-050-FR Accroître l’étendue des aires marines protégées pour assurer l’efficacité de la conservation de la biodiversité», consulted on 25 May 2022.

(3) The Marine Protection Atlas, “ Global Marine Protection“, 2021.

(4) K. Grorud-Colvert et al., “The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean”, Science 373.6560 (2021): eabf0861.

(5) Perry, Allison L., et al. “Extensive Use of Habitat-Damaging Fishing Gears Inside Habitat-Protecting Marine Protected Areas.” Frontiers in Marine Science 9 (2022): 811926.

(6) Perry, Allison L., et al. “Extensive Use of Habitat-Damaging Fishing Gears Inside Habitat-Protecting Marine Protected Areas.” Frontiers in Marine Science 9 (2022): 811926.

(7) Claudet, Joachim, Charles Loiseau, and Antoine Pebayle. “Critical gaps in the protection of the second largest exclusive economic zone in the world.” Marine Policy 124 (2021): 104379.

(8) Claudet, Joachim, Charles Loiseau, and Antoine Pebayle. “Critical gaps in the protection of the second largest exclusive economic zone in the world.” Marine Policy 124 (2021): 104379.

(9) L. Debeir and T. Lefebvre, “Analyse comparée des stratégies et des réseaux à l’échelle internationale”, p. 115, août 2019.

(10) Claudet, Joachim, Charles Loiseau, and Antoine Pebayle. “Critical gaps in the protection of the second largest exclusive economic zone in the world.” Marine Policy 124 (2021): 104379.

(11) Emmanuel Macron, “Déclaration de M. Emmanuel Macron, président de la République, sur la préservation de l’Océan mondial, à Brest le 11 février 2022“, vie-publique.fr, 11 February 2022.

(12) Ministry of Ecological Transition, “Projet de décret pris en application de l’article L. 110-4 du code de l’environnement et définissant la notion de protection forte et les modalités de la mise en œuvre de cette protection forte“, 14 January 2022.

(13) IUCN, “Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas,”2019.

(14) Kirsten Grorud-Colvert et al., “The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean,” Science (2021): 373.6560,

(15) The IPBES identifies overfishing as marine biodiversity’s main threat. (IPBES, “Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services,” 2019) Furthermore, the immense majority of captures result from industrial fishing. (Mariani et al., “Let more big fish sink,”2020)

(16) IPBES. “Biodiversity and Climate Change workshop report,” 2021.

(17) Interview with an OFB (French Office of Biodiversity) personnel